The era of reactive medicine is over. A tidal wave of real-time data, unleashed by medical wearables and analyzed by artificial intelligence, has pulled healthcare into a proactive new reality. For leaders, the question is no longer about the data's importance. The urgent question is whether our clinical systems, operational models, and governance can learn to swim in this new ocean of information.

Simon Beniston is a multi-award-winning entrepreneur and the Founder and CEO of MediBioSense Ltd, a medical wearable technology company that has delivered its solutions to over 58 countries. Drawing on a background in mobile application development for clients like Virgin and the NHS at CSC, Beniston is now focused on the new wave of predictive health. For him, one of the industry’s biggest challenges stems from a misunderstanding of what the technology can—and can't—do.

"At Northwell Health, they were able to predict severe deterioration in the patient roughly seventeen hours before it happened. That's massive. It tells you, with hours to spare, that a major decline is already underway," says Beniston. For him, that seventeen-hour window shows what proactive care can look like once real-time data becomes the default.

Beniston says the same predictive pattern keeps emerging across completely different use cases. In a trial with an Olympic athlete, their system flagged a high risk of sudden death syndrome in the middle of the night, long before she felt anything unusual. A study at Mount Sinai showed similar results, with the model identifying a bowel flare-up four days in advance. Taken together, these examples show how continuous biosignals can reveal looming clinical issues hours or even days before symptoms appear, giving care teams a window they have never had before.

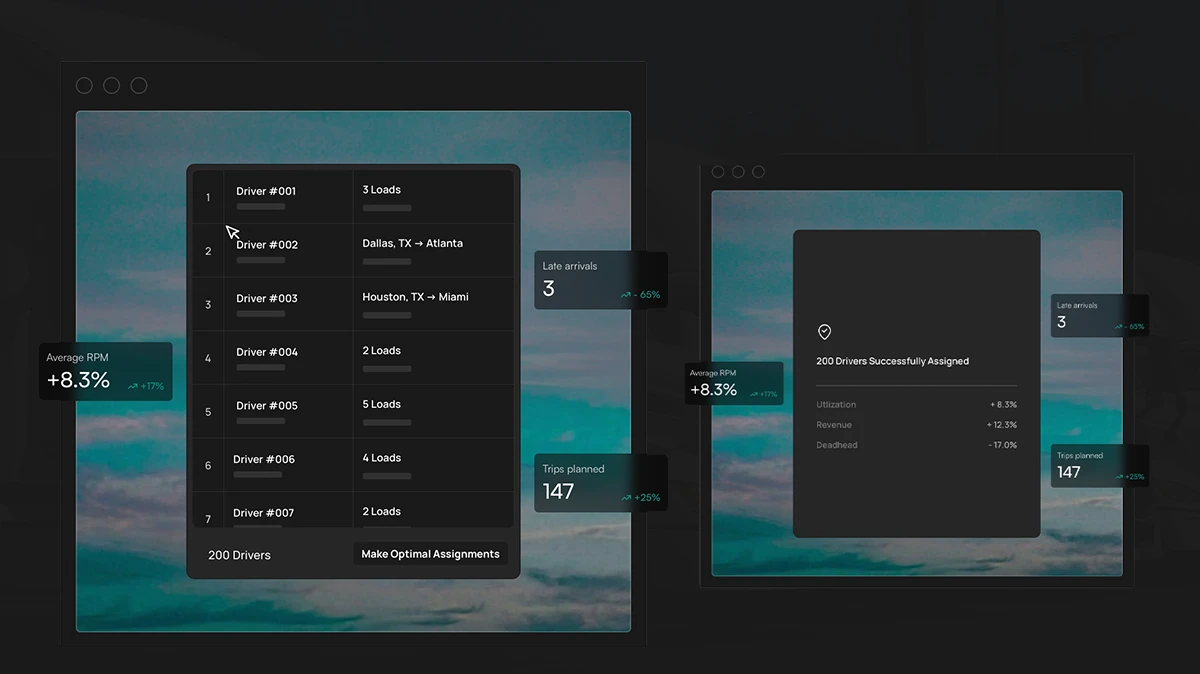

Drowning in data: According to Beniston, the leap in predictive capability comes from the sheer density of real-time measurement. While a hospital might take vitals a few times a day, "we're measuring ten vital signs every second with wearables," he says, which means more than 864,000 data points in a single day. "It becomes a data play. Even without AI, you can actually see a patient becoming ill. And with AI, a full cardiac report can be generated in eight seconds."

All pattern, no context: The challenge is that the volume cuts both ways. "AI almost finds too much. It can spot a pattern, but doesn't understand what was happening in the moments around it," says Beniston. He explains that the system might flag something like atrial fibrillation, "but it can't see the bigger picture or recognize that the patient was running, or that the signal was noisy. You still need a clinician to look at the alert and decide whether it's a real medical problem or something the system misread."

Mission possible: Beniston sees the solution as a two-part shift. "A key part of the fix is moving into a personalized care model, because healthcare still treats everyone the same even though we're totally different," he says. The second piece is turning raw insight into direction. "What a nurse needs is a mission outcome, a clear instruction on exactly what to do," whether that means repositioning a patient or administering a specific drug. And, as he put it, "when you get to that level of instruction, it better be right."

While his team has engineered a technical architecture meant to minimize risk, Beniston says the real bottleneck sits elsewhere. The toughest challenges aren’t computational but institutional, shaped by how healthcare organizations interpret, govern, and sometimes misunderstand the technology.

Anonymous at the source: "Our model is built on one core principle: do not store any patient-identifiable information. We only measure a unique device ID, a timestamp, and a string of anonymous data. The hospital's secure system is responsible for matching that device ID to a patient record," he says.

Lost in translation: Many of the sticking points come from long-standing assumptions about how data must be handled rather than the reality of how the system works. "The real issue is often with the hospital and the doctors. They will insist on having a server located in-country for data sovereignty, and I have to explain that it isn't truly necessary when the data is anonymous," says Beniston. "People are very focused on data privacy, but they are often not educated on what the technology actually does or what regulations require."

Ultimately, Beniston’s view circles back to a simple point: the technology is mature, the potential is enormous, and the real work now lies in aligning people, processes, and clinical practice. Progress depends less on new models and more on improving contextual judgment, integration workflows, and the way institutions interpret the tools in front of them.

Standing in the way is a maze of global regulations and country-by-country standards that slows adoption far more than any technical constraint. "The world is a small place, but our standards make it feel massive," Beniston concludes. "If we had one clear framework, these capabilities would scale almost overnight."