Enterprises are sprinting into AI, but many are sprinting in the wrong direction. The failure is in the mindset: too many organizations still treat data as a post-transactional IT artifact, then try to bolt agentic workflows on top and call it transformation. That’s how teams end up automating yesterday’s mess at machine speed, with dashboards and "insights" that rarely change what happens at the point of action. The fix starts earlier: put data ownership in the business, treat data as something deliberately designed to guide decisions, and use AI to rethink how work gets done rather than patch what’s already broken.

Dinand Tinholt, Global Head of Consumer Products, Retail, and Distribution Market for Capgemini's Insights & Data Global Business Line, has spent decades driving data-powered transformation across consumer products, retail, and manufacturing. He argues that enterprise AI is faltering because data is treated as an output of the business, not a business-owned input that shapes decisions before action is taken.

"You have to start thinking about data in a pre-transactional way, owned by the business, and create data products that drive your business as opposed to data that’s just the result of your business," says Tinholt. Designed this way, data stops being a byproduct of operations and becomes a mechanism for changing behavior at the moment decisions happen.

Decision intelligence: Tinholt applies the same logic to business intelligence, where he sees comfort masquerading as progress. "Business intelligence and BI reports are a bit like adult coloring books for executives," he says. "They’re nice, peaceful, and very therapeutic, but they don't move you forward." Dashboards may be polished, but when they fail to change decisions, they offer reassurance rather than direction. "I don’t care about business intelligence," Tinholt continues. "I care about decision intelligence."

Faster chaos: That same short-term thinking shows up in how many organizations deploy AI. Rather than questioning whether existing systems make sense, Tinholt says companies rush to automate them, mistaking activity for progress. "It’s just taking the existing process and saying, 'Can I replace a human there, or get a bit more efficiency?'" he explains. "That’s kind of like RPA 2.0, and it’s not being creative." The result is what Tinholt calls faster chaos: old problems executed at machine speed, with AI reinforcing broken logic instead of challenging it.

The real path to transformation, Tinholt advised, begins not with technology but with simplification. Before a single algorithm is deployed, leaders must first challenge the logic of their existing operations. This requires a disciplined, foundational approach that prioritizes clarity over speed. Only then can AI be applied not as a patch, but as a powerful tool for intelligent redesign.

Systems thinking cap: "The first thing you really need to do is look at what process you’re running. Can you eliminate and standardize it first?" Only then does automation make sense, says Tinholt, following a sequence he describes as eliminate, standardize, automate, robotize, and optimize. "Don’t treat it as a plugin. Treat it as a design tool and take a systems thinking approach."

No more excuses: One of the biggest barriers to real transformation, Tinholt argues, isn’t technology but bureaucracy. Risk, compliance, and governance are necessary, but too often they’re used to protect the status quo rather than enable progress. "We do these initiatives and hide them behind 17 layers of governance," he says. "Legal has to sign off, risk has to sign off. Governance and risk are being used too much as an excuse to not do some things."

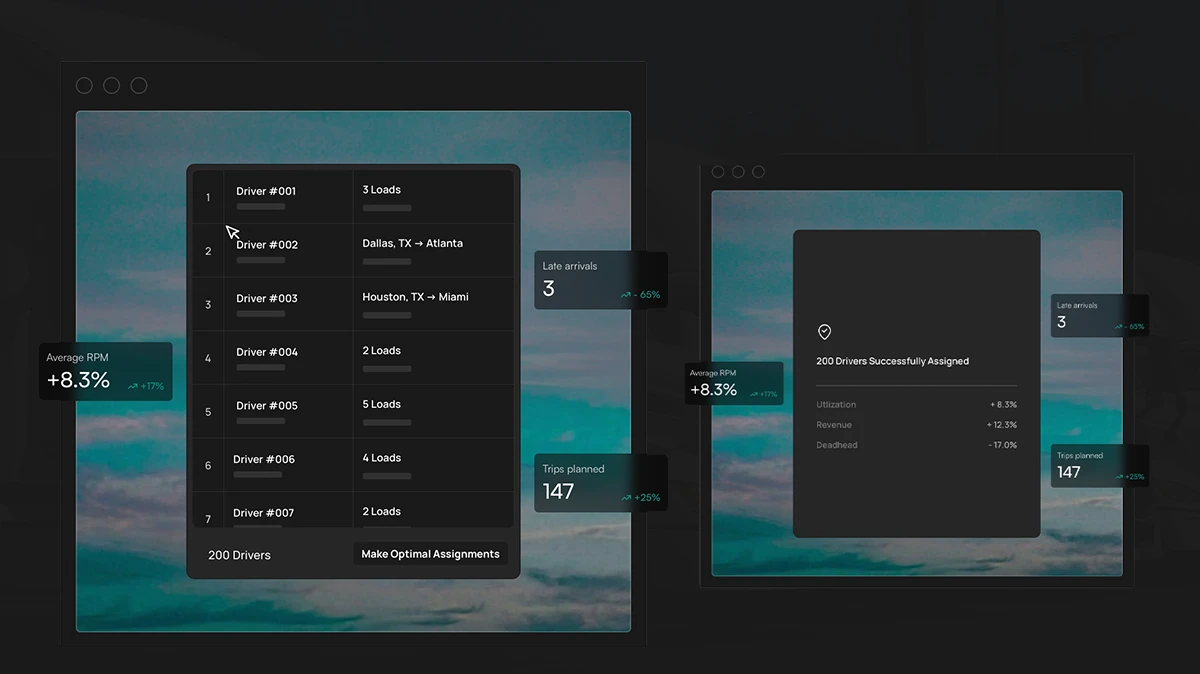

To counter this, Tinholt proposes a practical model for building trust incrementally. Rather than demanding a leap of faith, organizations should design systems that allow humans to validate AI-driven proposals before granting full autonomy. This phased approach turns skeptics into partners by giving them the tools to verify the logic and build confidence over time.

Building trust by foot: "When we propose to have AI take over certain decisions, we’re not actually handing it full control," notes Tinholt. "We have AI propose the decision, then a human clicks 'implement.'" Over time, organizations can raise the thresholds for autonomy as confidence grows. That strategic patience matters, Tinholt warns, because standing still carries its own existential risk.

Ultimately, becoming a data-powered enterprise means resisting the urge to automate dysfunction. AI’s real value isn’t in making broken processes run faster, but in exposing the flawed logic behind them and forcing a harder conversation about what should exist at all. "We don’t necessarily need faster processes," Tinholt concludes. "We need smarter ones, different ones. Sometimes we need fewer ones." Used correctly, AI isn’t a blunt instrument for efficiency. "It’s a scalpel, not a sledgehammer."