A fundamental change is underway in AI governance, signaling a move away from static compliance checklists and toward continuous, embedded operational models. The reason is simple: as AI agents become more autonomous and unpredictable, they introduce risks to business, reputation, and security that older frameworks were never designed to handle.

To understand this transition, we spoke with Siva Puvvada, Solution Director at HCL Technologies. He brings more than 22 years of experience in IT consulting and enterprise architecture for Global 500 firms, with senior roles at HCLTech and EY. Puvvada now focuses on AI Governance and Risk Operations, and his work includes AIGP® candidacy and the creation of a tamper-proof audit component on the Pega Marketplace. His experience gives him a unique perspective on how to build trust in these new automated systems.

His solution is a simple but profound analogy. "We should treat AI agents like digital coworkers, giving them identity, accountability, and oversight just as we would a human team member," Puvvada says. He explains that AI’s probabilistic nature creates a challenge that governance for predictable systems, like RPA, never had to address. Because AI models can infer, learn, and change, their behavior is inherently less certain. That uncertainty can render traditional access controls insufficient, making a new, identity-centric approach a high priority.

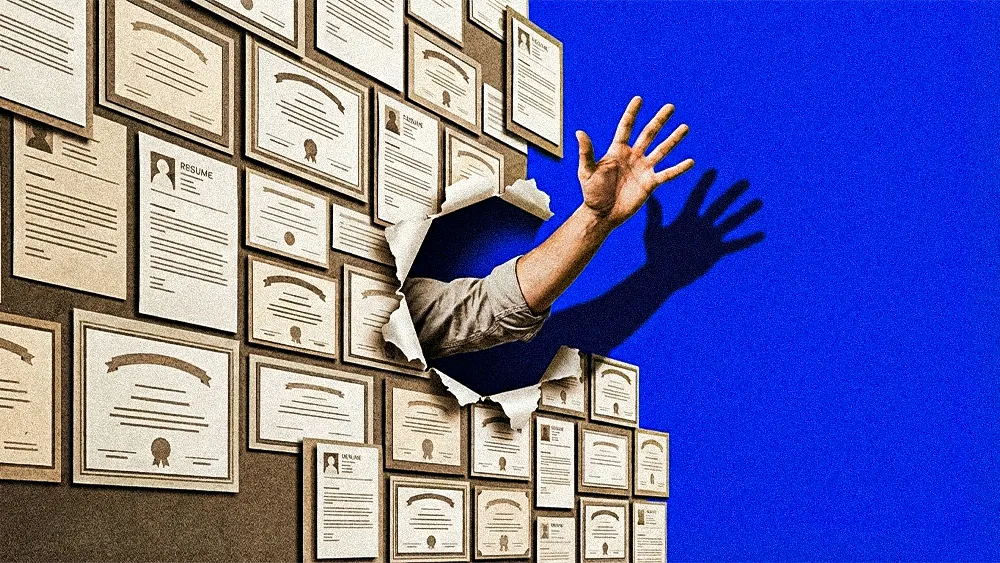

A BGV for bots: For Puvvada, the solution begins by modeling AI governance on established human resources processes, starting with a formal onboarding to combat “shadow AI," the invisible risk of tools deployed without centralized awareness that can undermine compliance foundations. "Governance for AI should be treated like a background verification for a new hire," he says. "That verification process means checking that the agent has a clear identity, the right tools, and the correct permissions to use them. And just as important, it cannot access tools for functions outside its designated role."

The accountability gap: Then there’s the blame game. Without a designated owner, organizations struggle to assign responsibility when an AI makes a poor decision, creating friction that stalls progress and demands systems capable of producing evidence-based audit trails. "The most prevalent gaps I see are ‘shadow AI,’ where organizations lack a basic inventory of their AI, and friction around accountability. You have to attach a human steward to every agent to establish clear ownership," Puvvada contends. "You cannot have a situation where the AI is simply blamed for a decision while no one is held responsible. This lack of accountability is what inhibits the scaling of AI."

For such a model to work at scale, governance must be baked into the code. By translating rules from frameworks like the EU AI Act or standards like ISO/IEC 42001 into machine-readable formats, organizations can enforce compliance automatically. That concept of policy-as-code is the bridge that allows companies to move from pilot projects to enterprise-wide deployment. But embedding governance in code doesn't solve the question of who owns it. A similar ambiguity can be seen in how organizations are choosing to structure their governance teams.

Finding a home: Puvvada notes that companies are still experimenting, with the function often residing in either the "data tower" or the "GRC tower," and no clear consensus has emerged. "No one has the right answer yet for where AI governance should live. But I believe enforcement will eventually trickle down to become the responsibility of every development team through the deployment pipelines," Puvvada predicts.

Calling all chiefs: These gaps are pushing many leaders to take governance seriously, as the consequences of failure can ripple across the C-suite. The risks are particularly acute in the financial sector, where regulators are scrutinizing the use of agentic AI. "Because of its probabilistic nature, AI governance failures affect the entire C-suite," says Puvvada. "If you fail to adhere to regulation, you face hefty fines, which impacts the CFO. If an agent shows bias, it becomes a reputational brand issue for the CMO. If prompt injections are not handled, you expose the attack surface, and that involves the CIO. Its impact is felt from top to bottom." This pressure is helping to fuel a wider move toward more skeptical, zero-trust governance strategies and is beginning to influence vendor selection, partnerships, and even M&A transactions.

The "digital coworker" lifecycle also includes a dangerously overlooked phase: continuous supervision. Puvvada notes that many organizations focus on pre-deployment "AI red teaming" but have a major blind spot for monitoring models once they are live.

Another issue is that pre-deployment testing only validates performance at a single point in time, failing to account for "model drift." This is when an AI's performance can degrade as conditions change over time, making continuous governance an important business consideration. "We have to monitor these drifts and ask: is the model that was deployed six months ago still relevant today? The world changes, regulations change. It is very important that this monitoring is properly thought of. Think of it as the AI's performance review," says Puvvada.