The White House has officially fired the starting gun on America's AI race, releasing a national AI Action Plan that serves as a high-level policy framework for driving innovation. But while the federal government charts the course, a chasm is widening between policy ambition and on-the-ground execution. The real front line in America’s AI race is the fractured industry-academia partnership, where a failure to turn abundant data into actionable insight stalls progress before it starts.

Paul S. Lavoie is the new Vice President of Innovation and Applied Technology at the University of New Haven. Drawing on his recent experience as the first-ever Chief Manufacturing Officer for the State of Connecticut to architect a new model for university-industry collaboration, his mission is to bridge the gap between two worlds that speak different languages. He argues the entire premise of the AI adoption problem is flawed.

Data rich, interpretation poor: "The bottleneck is knowledge, and we haven't figured out the intersection of computer science and advanced manufacturing yet. I talk to manufacturers and they'll say, 'We don't have a data problem. We have a data integrity problem, but we also have a data interpretation problem.' If engagement, education, and enablement are the three steps, education covers AI basics. But enablement means knowing where the benefits are and how to process all that information."

For Lavoie, the true barrier to AI adoption is not a lack of data, but a crisis of interpretation. The manufacturing sector is drowning in information it cannot use, a challenge he says is far more about human insight than technological infrastructure. This is where he believes traditional university partnerships have failed, and where his new model at the University of New Haven is poised to make a difference.

Proactive vs. reactive: "We can't be solving for solutions that industry thinks they need; we need to be solving for problems that exist in the industry. When industry comes to you with a problem and they think they have a solution, it's a very narrow band of thinking. We can't just have them come to us after they've already identified the problem and the solution, because that puts us in a reactive stage instead of a proactive one."

The proactive model is about more than just better projects; it’s about national competitiveness. As the current administration pushes to reshore manufacturing, Lavoie argues that the U.S. can’t compete on subsidized labor or materials. The only path forward is to become radically more efficient, and AI is the key—not as a tool to be implemented, but as a lens through which to understand and optimize entire systems.

The global imperative: "If we are going to bring manufacturing back to the U.S., we need to make it more cost-effective and more efficient. We can't compete with foreign governments that subsidize their manufacturing sector, like China subsidizes raw materials, energy, and labor. We're going to have to look at investing in software and tools that will make us more cost-effective and efficient so that we can compete on a global scale, and AI is going to be at the center of understanding what those tools are."

Of course, solving the knowledge problem creates downstream challenges. AI adoption demands immense energy and data infrastructure, a burden too great for any single state to bear alone. This reality has prompted federal action, such as the recent Executive Order to accelerate data center permitting, but Lavoie contends the approach is incomplete. The real challenge is political, rooted in a system that incentivizes competition over collaboration.

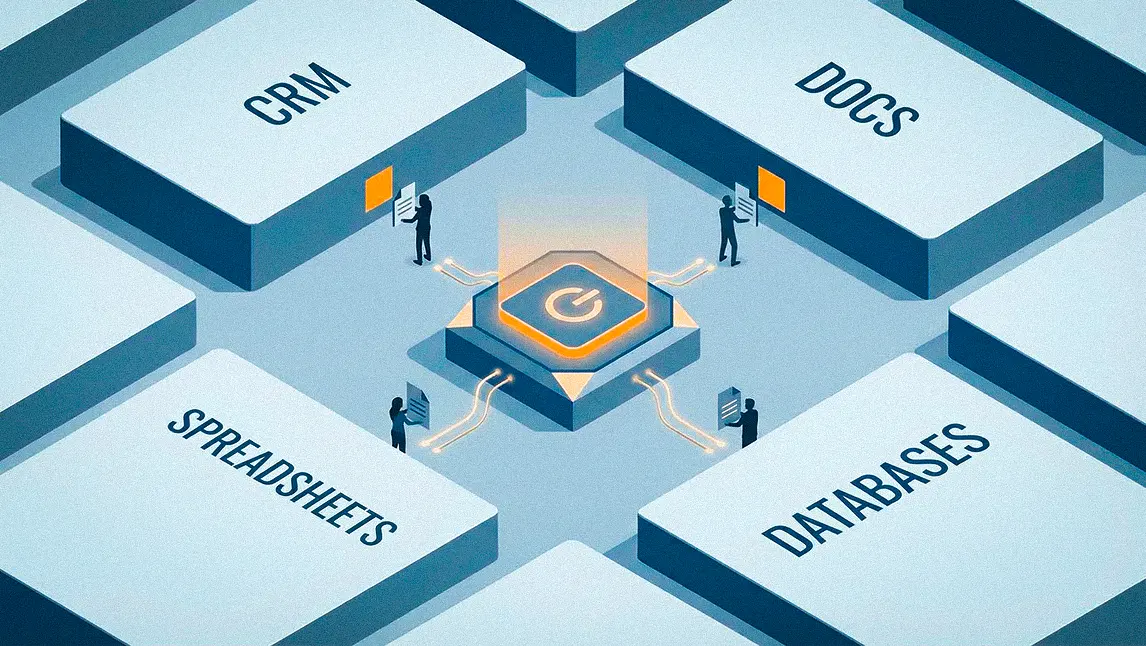

To make these partnerships sustainable, Lavoie's plan for a new business model at the University of New Haven's R&D Park could redefine the university's role entirely.

The partnership model: "We're not looking at this as a real estate model where you can come and rent space. What we're looking at is a center of excellence with a subscription model, looking at academia as an extension of the R&D departments within companies. The objective is to help industry innovate and grow, and along the way, we'll make sure students get jobs and that we're providing value back to the industry."

Lavoie’s vision is a direct indictment of a broken system. As Chief Manufacturing Officer, he saw both sides failing. His solution starts with a simple lesson: “When you’re fishing, if you want to be successful, you should fish where the fish are.” He recounts using the parable with manufacturers struggling to find engineers, asking about their ties to local universities. Often, there were none. And when he made the connection it rarely lasted, “because the university didn’t know how to best manage industry.”

Fixing that broken dynamic is now his life's work. It's a shift in mindset that he believes will unlock a tidal wave of opportunity, creating a national model for how academia and industry can finally build the future together. "When we do, we're going to run out of students before we run out of opportunities here at the University of New Haven," he says. "The need is that great, and the opportunity is that wide open."